Animal and wind power may have laid the foundations for the early development of internal combustion engines but nothing quite changed the world like the discovery and evolution of steam power.

The beginning of the steam power story is best associated with the discovery of the steam cylinder by Denis Papin in 1690. From this point, the “fire power” chain has never been broken, with continuity between Papin’s invention and the latest ultra-efficient internal combustion engine and the latest ultra-modern aircraft and rocket engines.

During the 17th century in Europe – the Age of Enlightenment – different geniuses including Evangelista Torricelli, Otto von Guericke, Gaspar Schott and Robert Boyle started preparing the playground, particularly through the study of the characteristics of the vacuum and its associated possibilities.

Denis Papin, a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, became interested in using a vacuum to generate motive power, especially while working with Christiaan Huygens and Gottfried Leibniz in Paris in 1663. Papin worked for Robert Boyle from 1676 to 1679 in London, publishing an account of his work in Continuation of New Experiments (1680), and gave a presentation to the Royal Society in 1689.

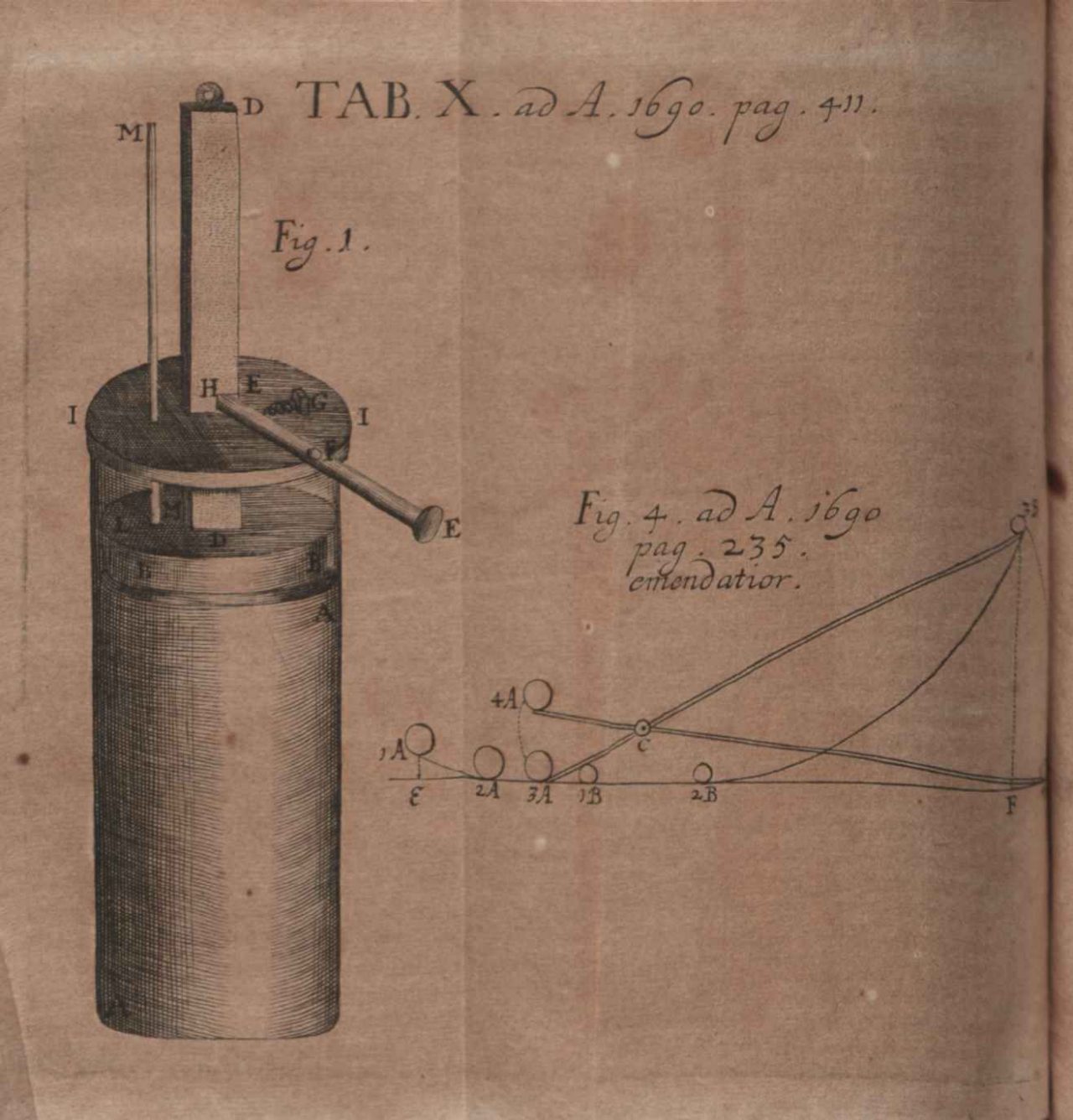

From 1690, after moving to Germany, Papin began experimenting with a piston to produce power through steam, building model steam engines. He experimented with atmospheric and pressure steam engines, publishing his results in 1707. It was during testing with his other famous invention – the digester – that Papin realized that the power of fire could be turned into useful work through steam. Papin also built the first steam powered ship (and vehicle) with his engine (Kassel 1704).

An illustration of Papin's piston-powered steam engine

An illustration of Papin's piston-powered steam engine

From invention to an operational working machine

Before and during the first investigations of Papin, other inventors, such as Spaniard Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont in 1606, also started elaborating ideas for the use of steam power, especially for pumping water in mines.

The first commercial steam-powered device was a water pump, developed in 1698 by British engineer Thomas Savery under the name of ‘The Miner’s Friend’. This kind of thermic syphon used condensing steam to create a vacuum, raising water from below and using steam pressure to raise it higher. Aside from taps, the machine didn’t have any mobile parts. Small engines were effective, though larger models proved problematic. They had a limited lift height and were prone to boiler explosions. Later, Portuguese scientist Bento de Moura brought significant improvements to Savery’s machine.

When he returned to England in 1707, Denis Papin was asked by Isaac Newton (president of the Royal Society after Papin’s friend, Robert Boyle) to work with Savery to improve his machine, which he did for five years.

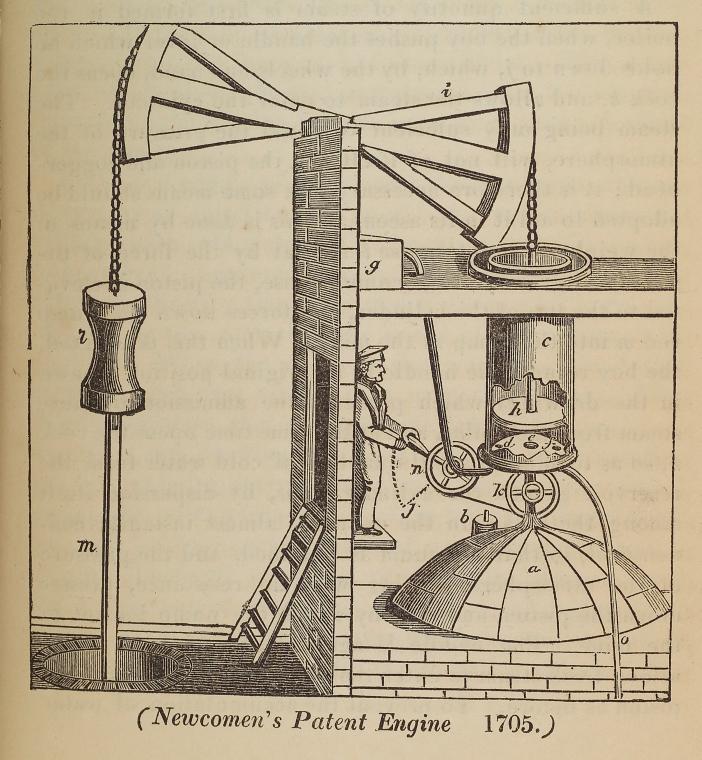

English inventor Thomas Newcomen was responsible for the real starting point for steam engines, however, in 1712. The aim was still to pump water from the bottom of deep mines, and Savery’s machine was still the foundation. This time, Newcomen was able to use Papin’s idea of a piston in a condensation cylinder, and to turn it into a real working machine.

More precisely, the idea was to fill a cylinder with the steam coming from a boiler, pushing the piston toward top dead center at a pressure slightly higher than atmospheric pressure. Then, water was directedly injected into the cylinder, condensing the steam and creating a partial vacuum. The atmospheric pressure – now higher than the cylinder pressure – pushed down the piston and created the working stroke. This is the reason these engines were called ‘atmospheric engines’.

The fact Newcomen was ironmonger and/or metal merchant would have given him significant practical knowledge, especially when bringing Papin’s machine from one cycle to cyclic operation, and according to Society of Gentlemen (1763) in 1712 the first example was already able to raise water from a depth of 91m, replacing 500 horses.

As explained, the Newcomen machine was still an ‘atmospheric engine’, which means that during the working stroke, the cylinder pressure remained at a lower level than the atmospheric pressure, with no risk due to high steam pressure. Efficiency, however, was still very low, at just one to three percent.

Newcomen's patent engine, 1705

Newcomen's patent engine, 1705

How British inventors and engineers triggered the first industrial revolution

Newcomen’s machine was already operational, and a large number of them were used throughout European mines during the first half of 18th century, but still with limited efficiency and power density.

The first big improvement to this machine was brought by James Watt between 1763 and 1775, by removing spent steam to a separate vessel for condensation, greatly improving the amount of work obtained per unit of fuel consumed. Watt’s next improvement was to circulate the steam around the cylinder, helping to prevent any condensation.

Watt used both sides of the piston (double effect), by expanding the steam from a moderated pressure down to atmospheric pressure, before opening the connection to the condenser, and the ‘Watt parallelogram’ enabled the double effect piston to be used for alternative pumps. James Watt also patented the high pressure cycle as having a better potential (1782), but he was aware of the related risks, mainly because of the lack of technological maturity.

By analyzing the steam circuit of the Newcomen’s machine mock-up, Watt’s improvements multiplied efficiency by two to three times. Watt also patented a ‘sun and planet’ gear system that used alternative steam machines to provide rotative power, with the potential to replace water and wind mills used to power factories.

Even bigger things were to come, as humans embraced steam machines for motive power, but the technology would have to improve a lot further, even after James Watt’s developments. Thankfully some incredibly clever people were more than up to the task, and you can read more about how steam machines evolved into the direct ancestors of the modern internal combustion engine in our next installment next week.