Büchi was well-placed to become a major influence in engineering. He was the son of a chief executive at Sulzer, the Swiss engineering and manufacturing giant, which was already a well-established company at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1899, he enrolled at ETH Zurich, a public research university, to study machine engineering. Then, having graduated, he worked as an engineer abroad in Belgium and England, before returning to Switzerland in 1908.

Alfred Büchi, inventor of industrial turbochargers

Alfred Büchi, inventor of industrial turbochargers

An idea that changed everything

During his time abroad, in 1905, when he was just 26, Büchi filed a patent in Germany for a “highly supercharged compound engine” with a diesel engine, axial compressor and axial turbine mounted on a common shaft.

An extremely experimental idea at the time, neither the materials nor the fuels yet existed to turn Büchi’s idea into reality. Notwithstanding, the patent covered the fundamentals of every turbocharger created since: a turbine fed with exhaust gases is spun at high speed to pull fresh air through a compressor into the ignition chamber to boost the engine’s performance and lower fuel consumption.

The early twentieth century was a period of enormous innovation in engineering. The Wright brothers made their first powered flight in 1903; the Ford Model T was introduced in 1908; stainless steel was invented in 1913; the Panama Canal was finished in 1914. Reinforced concrete, the factory assembly line, broadcast radio and intercontinental telephone calls also all made their first appearance during this short period.

In parallel, during this period, the idea of turbocharging engines was gaining support and the practicalities of their creation were being solved. But initially, they were targeted towards the new field of small, lightweight aircraft engines, with successes in boosting performance achieved in planes in the United States and France. People didn’t yet see their application for larger, slower industrial engines, thinking that they would not be economically viable.

Realizing the dream: 1924

Büchi worked on diesel engines for Sulzer during this period, though he’d also started a dialogue with the up-and-coming Swiss engineering firm Brown, Boveri & Cie (BBC), Accelleron’s direct ancestor, to see if they might cooperate in bringing his ideas to life.

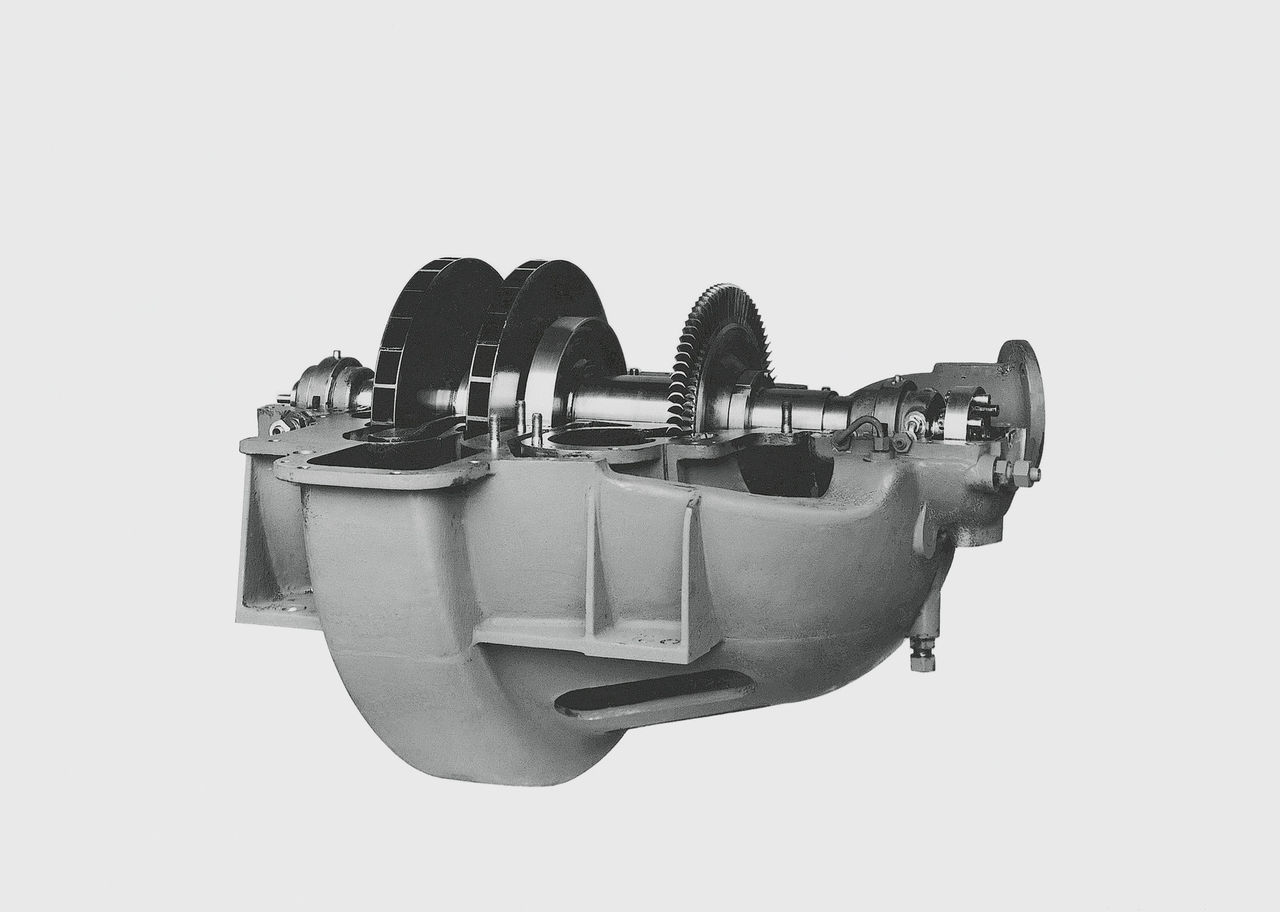

In 1923, BBC received an enquiry from the Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works. They had developed an experimental two-stroke engine for diesel trains. The engine needed to deliver more power and deliver better fuel consumption. BBC suggested using an exhaust gas turbocharger and SLM agreed to the deal. In June 1924, the VT402, the world’s first heavy-duty exhaust gas turbocharger, was completed at BBC’s Baden machinery works.

The VT402, the first turbocharger for large engines

The VT402, the first turbocharger for large engines

Meanwhile, the marine industry also coming round to the idea of turbochargers. In 1923, the Vulkan shipyard in Germany had ordered two large passenger liners – the Preussen and Hansestadt Danzig – each of which was to be powered by two turbocharged 10-cylinder, four-stroke MAN engines. The turbochargers were designed and built at BBC under Büchi’s supervision. Launched in 1926, these two ships were the first in history to have turbocharged engines.

The invention and commercialisation of the turbocharger is an achievement that laid the foundations for the development of the modern economy as we know it today. It would not be possible to generate the engine power we require using the resources we have without its existence.

A century of improvement

Several elements of the story are extraordinary. The first is the way the fundamentals of turbocharging were set out in one sweep, right from the start. Using otherwise wasted exhaust gases to draw fresh air to make the engine work better is one of those ideas that appear simple and obvious, But at the same time, until Büchi put them on paper, no one had put the dots together.

The second is that while the most desired objectives from turbocharging have changed over the years, from engine performance, to fuel efficiency and now to reducing emissions, the principles and shape of the turbocharger is essentially the same. Its performance characteristics, materials, geometry and construction have all been continuously improved, but the basic principles remain the same.

The final piece of continuity is that partnerships between manufacturers and specialists have been a feature of the industry since these early years. Innovations are only rarely the product of one mind. Büchi was undoubtedly a genius, but without the cooperation of BBC to create his products and of engine makers to put their faith into the ideas, nothing would have happened. This same web of ideas, manufacturing and creating solutions for customers continues to drive innovation in optimizing combustion engines to this day.